|

I'm so pleased to announce the pre-order gifts for We Are Not Free! With your proof of purchase (or proof of library request) for We Are Not Free, you can get:

To enter, submit the following to chee.preorders @ gmail . com (without the spaces):

***If you order from Books Inc. in San Francisco, you can get the whole set of six signed collectible bookmarks, as seen here! This offer is good while supplies last. You can order from any retailer, like Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, or your favorite local bookstore, which you can find at IndieBound! Just don't forget to send in your receipt! And now... a launch party!For my virtual launch this year, I'm partnering with longtime Japantown institution, the Japanese Community and Cultural Center of Northern California, and local Bay Area bookseller, Books Inc. Even though we can't all be together right now, it's such an honor to be working with these local organizations, and I hope you continue to give them your support!

Tuesday, September 1 at 6pm PDT with Misa Sugiura (This Time Will Be Different) and some very special surprise guests! Please register here for the Zoom link. I think we hear a lot about how "good" & "obedient" the Japanese Americans were in WWII, but the incarcerees were not a monolith. They were from diverse backgrounds & held diverse opinions, and rather than submitting to their unjust treatment, a great many of them resisted.

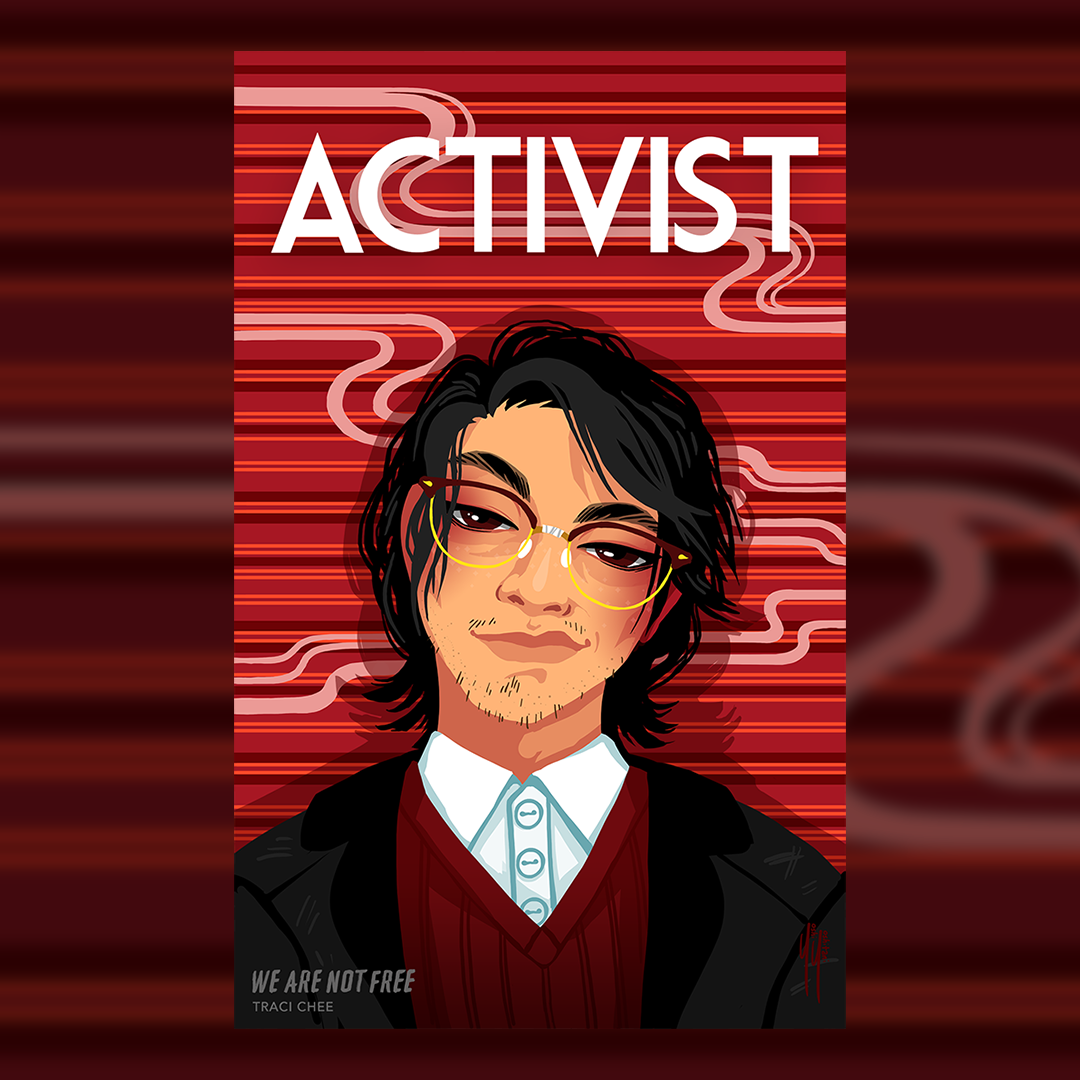

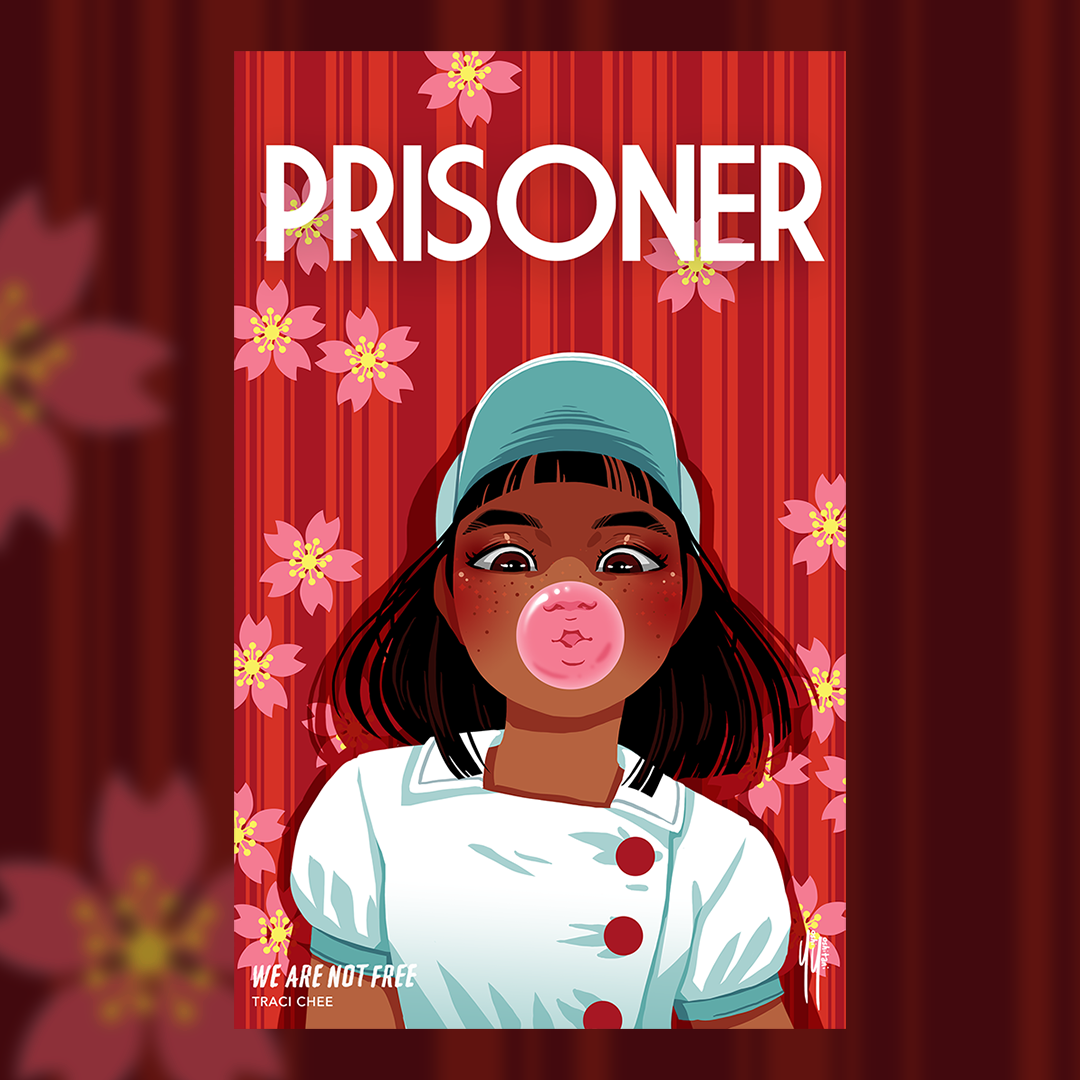

If you haven’t read the first three parts of this series, you can read them here: I) the mass eviction II) the temporary detention centers and incarceration camps III) the Japanese-American combat team * In 1943, nearly a year after the mass eviction that forced more than 100,000 Japanese Americans from their homes on the west coast, the US government announced that all incarcerees age 17+ would be required to register their names, backgrounds, and allegiances. This registration, which eventually came to be known as the “loyalty questionnaire,” soon became a source of great conflict among the incarcerees due to two questions: Question #27 asked incarcerees if they would serve in the US military, wherever ordered; #28 required them to “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor.” The wording of these questions led to weeks of confusion and controversy. Some feared feared a “yes” to #27 would enlist them in the military. Others criticized the registration as being “too little, too late.” Many first-generation immigrants were concerned that if they answered “yes” to #28, they would be stripped of their Japanese citizenship--the only citizenship they had--and thus become stateless persons. Some of their American-born children were affronted by the assumption that they’d ever been loyal to Japan in the first place. Despite all of these nuances, however, in the end the federal government accepted only two responses: Incarcerees either replied with an unqualified “yes” to both questions, or their answers were recorded as “no” and “no.” Throughout the late spring and summer of 1943, the divide between those who had answered “yes” and those who were branded “No-Nos” caused extreme tensions between Japanese Americans and with camp administrators. After several violent confrontations, some of which involved the deaths of incarcerees, the Japanese Americans were subjected to another forced relocation, as the “No-Nos” were shipped off to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a camp with higher fences, more soldiers, and heavier artillery to guard the so-called “disloyals” and “troublemakers.” Tule Lake soon became the largest Japanese American incarceration camp of World War II, with more than 18,000 incarcerees crammed into less than 1.75 square miles. Under conditions of overcrowding, inadequate facilities and food supplies, unsafe work environments, and the inevitable differences arising out of so large and diverse a population, Tule Lake became the site of strikes, unlawful detentions, fights, renunciations of American citizenship, and the rule of martial law. This history remains controversial and at times contradictory, but it’s clear that the Japanese American incarcerees were far from a homogenous group of quietly suffering victims. Some resisted their treatment through the due process of the law. Some organized community protests. Some refused to answer the loyalty questionnaire. Some were violent. Some burned their draft cards. Decades later, many of these stories are still emerging, and they continue to demonstrate that resistance is woven into the very fabric of the incarceration. Preorder your copy here or add it on Goodreads! Illustration by Yoshi Yoshitani. 8 WEEKS until WE ARE NOT FREE! Pre-order HERE and keep your receipts because I’m announcing pre-order gifts in a couple weeks! 🌻

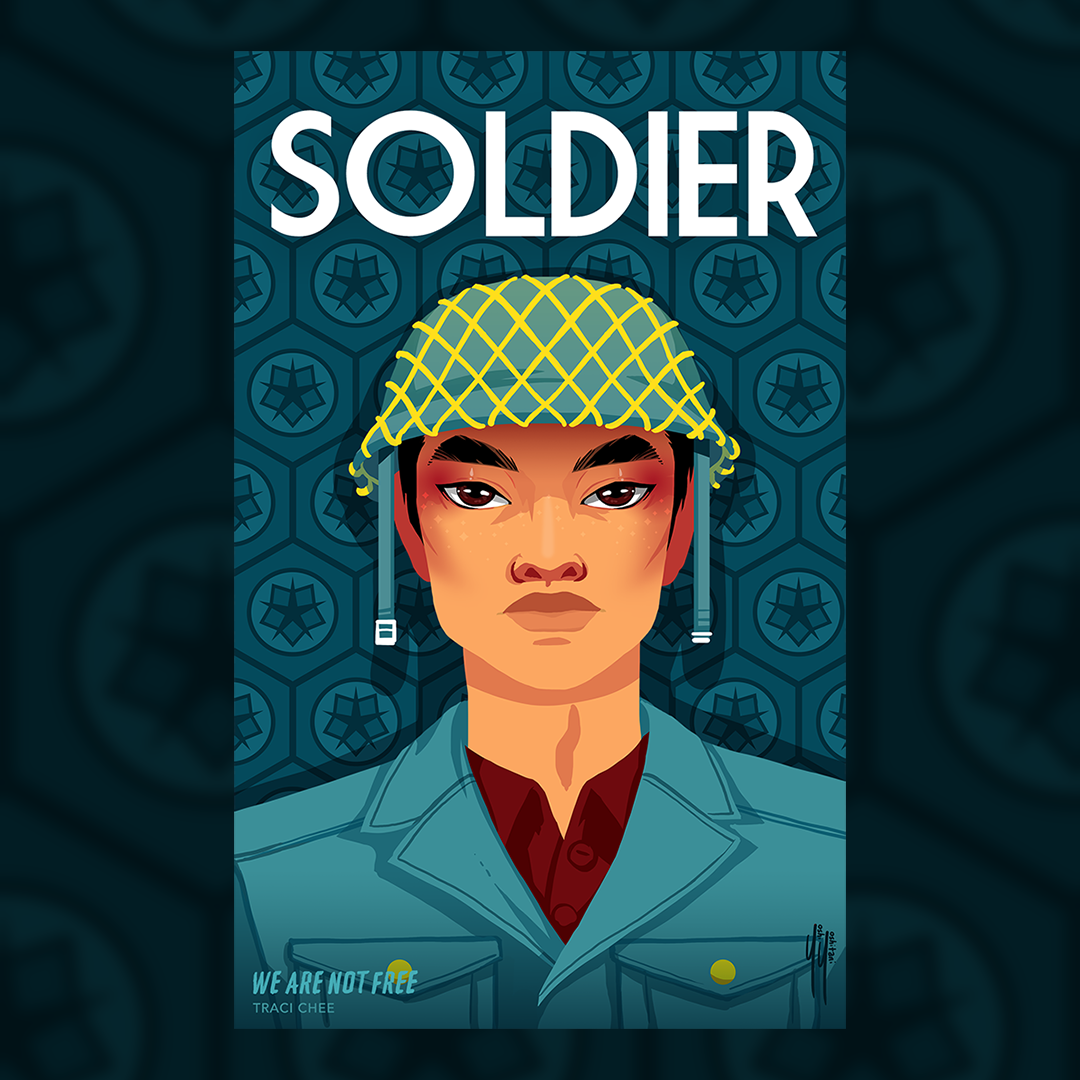

Despite their wrongful incarceration, many Nisei (2nd gen. citizens) volunteered for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Military Intelligence Service & Women's Army Corps. I couldn't include all of these in #WeAreNotFree, but I did want to talk a bit about the 442nd here...

If you haven’t read the first or second parts of this series, you can catch up below: I) the mass eviction II) the temporary detention centers and incarceration camps * Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the vast majority of Japanese Americans, including those who were US citizens, were classified as “enemy aliens,” a designation which denied them, among other things, the right to enlist in the armed services. The classification remained in place until early 1943, when the federal government declared it unlawful to deny any citizen the right to defend their country. This announcement coincided with a call for volunteers for an all-Japanese segregated fighting unit, which would, in theory, visibly and unequivocally demonstrate to the rest of the country the loyalty of the Japanese Americans they had incarcerated in camps. Critics were skeptical. Many feared that a segregated unit would be treated as disposable, and they were quick to point out the hypocrisy of asking Japanese Americans to fight for a nation that had not only stripped them of their civil rights but also continued to hold their friends and families prisoner. Nonetheless, almost 3,000 volunteers from Hawaii and an additional 1,500 from the mainland chose to enlist. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was activated in February 1943 and trained at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. In May 1944, they were deployed to Europe, where they met up with the 100th Infantry Battalion, composed primarily of Japanese American servicemen from Hawaii. Over the course of the next year, the 442nd fought in major campaigns in both Italy and France, including the rescue of the “Lost Battalion,” when 275 soldiers of the 141st Regiment, 36th Division, were trapped behind enemy lines in the Vosges Mountains. During the rescue, the 442nd suffered an estimated 800 casualties, at times fighting with less than half their normal strength, but after five long days of battle, they succeeded in breaking through enemy lines to the beleaguered soldiers of the 141st. The 442nd RCT later went on to become the most decorated unit of its size in American history. With an impressive 7 Distinguished Unit Citations, 21 Medals of Honor, more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, 29 Distinguished Service Crosses, 588 Silver Stars, and more than 4,000 Bronze Stars, it has become indisputable proof of not only the loyalty but also the skill and bravery of the Japanese American volunteers. As President Harry Truman said during a review of the 442nd in July 1946, almost a year after the end of World War II, “You fought the enemy abroad and prejudice at home and you won.” Preorder your copy of We Are Not Free or add it on Goodreads! Illustration by Yoshi Yoshitani. Continuing my brief series on the history of the Japanese American incarceration, I’d like to talk this week about the camps. When I learned about the conditions in these places, I was shocked. My family went through THAT? Lived through THAT?

Yes. They did. #WeAreNotFree If you haven’t read the first part of this series, you can check it out here: I) the mass eviction * After being forced from their homes in the spring of 1942, more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated in seventeen temporary detention centers throughout the western United States. Surrounded by barbed wire, watch towers, and armed soldiers, these American citizens and their immigrant parents were subjected to substandard living conditions on top of the stress and trauma of losing their homes. Many of the detention centers were former race tracks, where incarcerees were forced to live in horse stables, hastily white-washed and still stinking of manure--one family to a stall meant for a single animal. Suffering from both lack of privacy and of freedom, they ate in overcrowded mess halls, brushed their teeth in troughs, and used communal latrines and showers without partitions. Despite appalling conditions, however, on the whole incarcerees did what they could to make life more bearable. They built furniture out of scrap lumber, established schools and libraries, formed representative organizations to oversee camp affairs, held dances and concerts, and showed films. Later in 1942, incarcerees were shipped to more permanent camps farther inland. Located in desolate, isolated locations in eastern California, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas, the camps were composed of “blocks” of tar-paper barracks, dirt roads, and communal mess, bathing, and laundry facilities--all encircled by barbed wire fences. While conditions in the incarceration camps were generally better than those in the temporary detention centers, many incarcerees disembarked from cramped, stuffy train cars to find that the camp facilities were still incomplete, and their barracks lacked insulation, proper ceilings, and coal stoves for heat, or that their barracks had not yet been constructed at all. The Japanese Americans again attempted to make the best of their situation, planting gardens, forming cooperative stores, and finding other ways to occupy themselves with work and recreation. But the crowded confines, the knowledge that their civil rights had been violated, and the lack of assurances about their future in the United States caused unrest and conflict, both between incarcerees and with the white administrations overseeing the camps. For three years, until the exclusion orders were lifted in 1945, incarcerees were prevented from returning to the west coast, which meant that many Japanese Americans were forced to live, die, graduate, give birth, bury their parents, get married, forgo college education, learn to drive, and celebrate and mourn thousands of other milestones while unjustly imprisoned. Preorder your copy here or add it on Goodreads! Illustration by Yoshi Yoshitani. 2 MONTHS until We Are Not Free! ☀️ Over the years this mug has been stained and chipped and glued back together again, but it’s special to me because it features my Japanese family mon, or crest—it looks like a flower but it’s actually the inside of a melon! 🍈 To me, it represents family, belonging to a history, being a part of something that stretches back through time and blood, joy and love. 💚

Pre-order your copy here and don't forget to save your receipt to get your soon-to-be-announced pre-order gift!

I’m excited to share the education session I cooked up for Tadaima! A Virtual Community Pilgrimage: WE ARE NOT FREE: Teenagers in Topaz. In this session, I provide a glimpse into the lives of teenagers at the Central Utah Relocation Center, more commonly known as Topaz, where my grandparents and their families were incarcerated in World War II. Tune in for a mix of history, photographs, excerpts from the camp newspaper, family artifacts, and some illuminating anecdotes about young people’s lives in a Japanese American incarceration camp. Plus, my best impressions of my grandma and grandpa! ? Check it out here or view below!

|

ARCHIVES

February 2024

CATEGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed