|

Since my new (formerly) secret project, We Are Not Free, is out of copy edits and heading to the printers for advance reading copies, I’m charging full steam ahead into my New New Secret Project, which I alluded to outlining in Week 6, Planting the Seeds. This is an idea that’s been cooking in my head since 2017, which feels like a long time for an idea to percolate, although it’s taken less time than The Reader Trilogy (5 years) and We Are Not Free (5-21 years), and I’m so excited to be tackling it now. There’s nothing like the fresh energy of a new project, the delight in discovering a new world, new characters, a new story. It’s exciting! (It’s kind of terrifying.) This, in conjunction with our recent explorations of rhythm, have gotten me thinking about the rhythm of my drafting process. I think of it like repeatedly building a structure out of popsicle sticks. I lay the foundations. I take the foundations down. I lay the foundations again, this time a little larger, a little better, a little more like what I want the eventual structure to be. I take them down. I lay the foundations, again, a little larger, a little better, and maybe I add a first floor. Maybe I build some walls, with spaces for windows, doors, stairwells. I take them down to the ground again. I rebuild. I erase. I rebuild again, adding more and more words each time, until I feel good enough about those foundations that I don’t have to destroy them anymore. Now I delete back to the first floor, build again, delete and build again until I’ve reached the second floor, and so on and so forth. A caveat: I draft like this when I have the luxury (or illusion) of time. Often, the reality is that I just have to get the words down, just have to accept that they’re not perfect, just have to keep going because I’ve got a deadline to meet. But I do feel like it’s important for me, in the early days, to luxuriate in a project for a bit, to sink into it or swim around in it for a while, getting a sense of what kind of story it is, where it wants to go, what it wants to be. To give you an idea, here are work-in-progress screenshots of my first eight drafts of my New New Secret Project’s first chapter: Notice those false starts in the first three drafts? In each one, I got about as far as a page before realizing the foundations weren’t working, so I had to raze everything to the ground and start again. It isn’t until Draft 4 (four pages long), that I really begin to figure out how to tell this story, and even then, it takes another false start (Draft 5) before I begin to hit a stride with Drafts 6-8, adding a little more each time.

The above drafts are about 1-2 weeks’ worth of work, because I’ve I retyped each paragraph, changing a word here, a phrase there, a piece of punctuation this time or that, maybe 10-20 times before moving on. It is a slow, sometimes frustrating process, because some days--especially the ones at the very beginning--I end up with a 100-word gain on my previous word count. Or a 100-word loss. And it feels like I’m going nowhere, this project is going nowhere, I’ll never get it done. But retyping each paragraph, making dozens of little changes along the way, is how I get to know things like voice, character, atmosphere, conflict. I’m finding the rhythm of the story, from the action to the dialogue to the paragraphs to the sentences, and so each time I retype a passage, I’m “listening” for things like: the flow of one idea into another, where the narrator draws the reader’s attention, whether the voice uses high or low register diction, how the sentences come together, the balance between action/description/dialogue, the pauses. I can’t “hear” these things (or at least, I don’t “hear” them as well) if I look at each word/phrase/sentence/paragraph in isolation, the way I suspect most people do when they’re writing and revising. I have to re-enter the rhythm of the passage by rewriting it, literally, over and over again, like practicing a piece of music, until I’ve figured out how the story wants to be told. Last week, we began our craft-focused exploration of rhythm and how it operates at various scales in the text, from the larger paragraphs right down to the smallest punctuation. To continue that discussion, today I’d like to talk about rhythm on the level of the sentence, specifically sentence length. You may be familiar with this famous quote from Gary Provost: This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five-word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The writing is getting boring. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety. In this passage, the sentences have five words each, creating what Provost calls a “monotonous” rhythm. It feels, I think, the same way it would feel if each paragraph was the same length, or if we had a series of spondees (metrical feet with two stressed syllables one after the other) without interruption. Have you read A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle? This type of beat reminds me of IT’s inexorable, inescapable pulsing. Dun. Dun. Dun. Dun. On and on without respite. Take this paragraph from Chapter 8, wherein IT is “speaking” to Meg through the man with the red eyes about her brother, Charles Wallace, who has only just been possessed by IT: “But my dear child, you are hysterical,” the man thought at her. “He is right there, before you, well and happy. Completely well and happy for the first time in his life. And he is finishing his dinner, which you also would be wise to do.” Breaking it down, the sentence lengths go like this:

Although these sentences, unlike in Provost’s example, aren’t all exactly the same length, they are similar enough that they feel almost unnaturally even, unnaturally the same, which is IT’s ultimate goal, to flatten everything in the universe into sameness. When it comes to storytelling, then, using the same sentence lengths could be useful in underscoring situations where your characters are facing down an IT-like entity, or have stumbled upon a martial parade, or are hearing the drums of war, or are dealing in some way with dogma, indoctrination, brainwashing. Provost’s quote continues thus: Now listen. I vary the sentence length, and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length. And sometimes, when I am certain the reader is rested, I will engage him with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals–sounds that say listen to this, it is important. Here, varying sentence length makes the writing more interesting. These sentences are of different lengths, creating a more lively rhythm. Rather than the relentless drumming of the five-word sentences, we have rests (in the form of punctuation, which I’ll discuss in a few weeks), emphases (like “Music.”), riffs (like the list “a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony”), crescendoes (in which a sentence rolls on so long it feels like it’s running out of breath, and so it almost feels more rushed as it barrels toward the end). These elements, or perhaps techniques, all create rhythm at the sentence level. I’d go even further to say that not only does playing with sentence length create interest in the writing, it can also contribute to the storytelling. This is something I consider when writing fight sequences, for example, and I want the rhythm of the sentences to mirror the exchange of blows, so it’s as if the reader can feel the pace of the battle. For example, we can examine this passage from The Reader, pg. 243-244, where Archer, a boy who has been forced to fight and kill for the past two years of his life, is facing an assassin in the cargo hold of a ship: Across the hold, Archer slashed at the woman’s face, his knife flickering in the lantern light. The woman deftly stepped aside and cut him across the back of the arm. He retreated. His arm stung. His head was buzzing with the hot smell of metal. The lowest deck was packed with cargo, forming narrow walkways in the hold. Not much room to maneuver. Easy to get trapped. After last week’s discussion on paragraphs and rhythm, I’d like to point out how the first paragraph is chunkier--it drops us right into the middle of the fight, and the action, description, and Archer’s assessment of the situation are all kind of mushed together, emphasizing how chaotic Archer’s thoughts are as he faces someone who might be a better fighter than him. In the first two paragraphs, there’s this closeness, almost claustrophobia, to the fight, as the woman is on the offense, and the characters are forced together in battle, but then at the third paragraph, “They parted,” there’s this breath, this white space, like (I hope) dance partners going separate ways on a stage. Although when writing this passage, I didn’t count every word of every sentence, but I did want to be mindful of how long and short each sentence was. The sentence lengths break down like so:

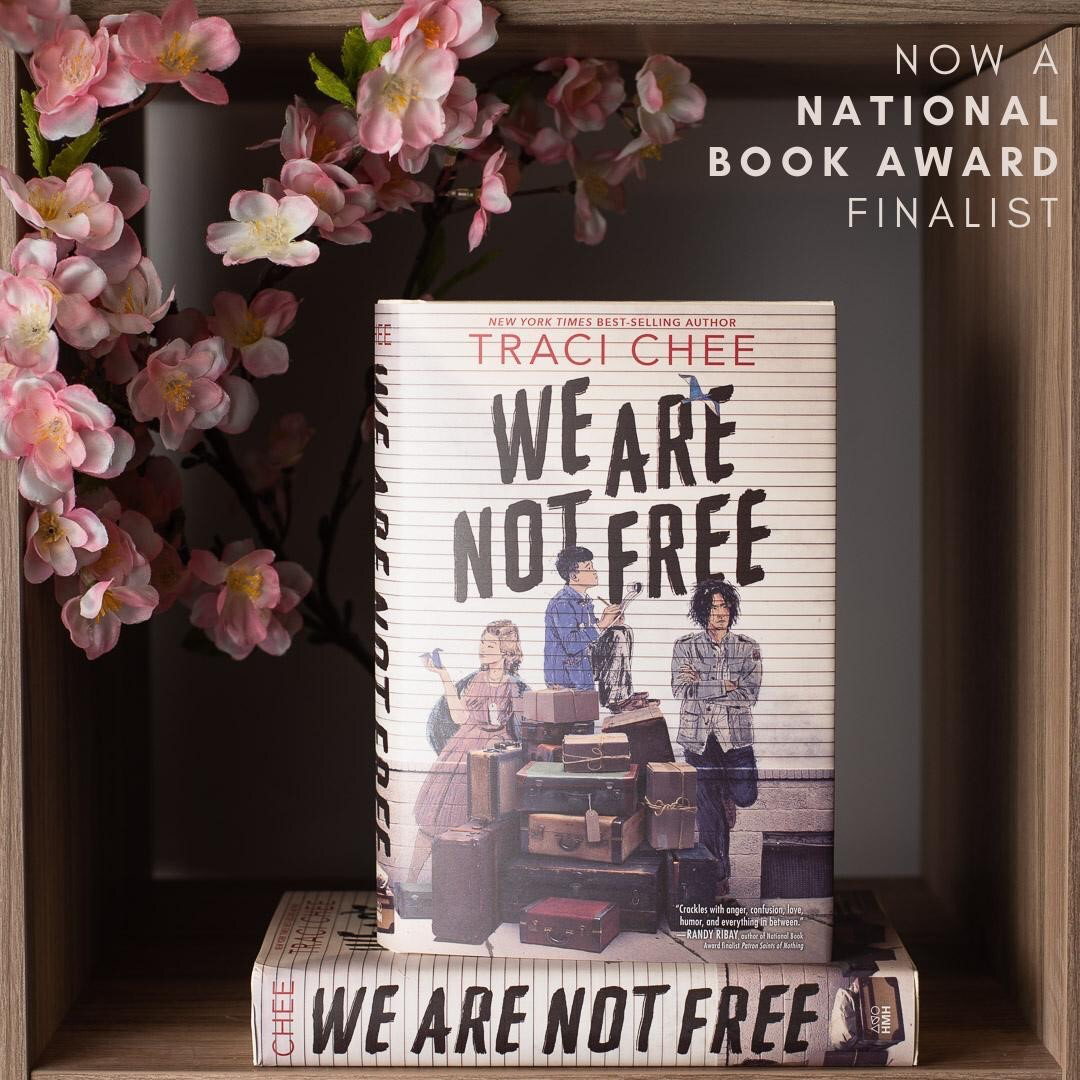

It’s interesting, now that I look at it this way, because I can clearly see a pattern: long, long, short, short, long, long, short, short… then: long, short, short, long. When the characters are actually engaged, the sentences are longer, cramming more action (like “attacking, slashing, stabbing”) into each sentence, which underscores how quickly this fight is going. Then, there are these moments of relief, almost, like panting breaths (“He retreated. His arm stung.”), as the fighters prepare to clash again. Although this pattern is subtle when the sentences are broken up into regular paragraphs, it’s actually pretty regular, which makes sense, because I wanted Archer’s fights to feel like a dance, like he knows the steps as if they’ve been choreographed for him, and even pattern to the sentence lengths underscores the rhythm of it, like the beats to a piece of music. Operating at these two levels (paragraph, sentence), the rhythm here tells us two different stories: 1) the rhythm of the paragraphs shows how quick and frenzied the fight is compared to the almost graceful rest they get when they separate, and 2) the rhythm of the sentences shows how, even though it feels chaotic and fast, it’s also all part of a pattern of blows and exhanges, and Archer inherently understands this rhythm, feels it, I suppose, in a way that doesn’t need logical explanation. In sum, rhythm at the scale of the sentence can add layers to your storytelling, felt more than consciously understood, and reveal layers to your scenes and characters without you having to make them explicit. As with paragraphs, longer sentences mean we linger on an idea or a detail, whereas shorter ones mean we skip over things more quickly, although they also feel more important because they stand on their own. Unvarying sentence lengths can alert your readers to the fact that something is wrong with the situation, for perfectly even rhythms are unnatural, perhaps unnerving. Patterns (or lack thereof) in the sentence lengths can emphasize the way characters feel or engage with a situation on an instinctive level. Up next: rhythm and diction! It’s here! The Nerd Daily is revealing the cover of my new novel, WE ARE NOT FREE, a YA novel-in-stories that follows fourteen Japanese-American teenagers through the mass incarcerations of World War II. Loosely inspired by some of my own family’s experiences, this story is so close to my heart, and I am so honored I get to share it with you now. Check out the link to find out more about my personal connection to the novel!

BONUS: You can also read the first chapter! 😱 Many many thanks to the brilliant people who put this cover together: designer Jessica Handelman, photo-illustration artist David Field of Caterpillar Media, and illustrator John Lee, who brought six of these characters to life with such vivid detail, and of course to the beautiful team at HMH Teen for making it all happen! Last week, I wrapped up copy edits on my secret project (which I can announce next Tuesday--check in with me on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to see my behind-the-scenes #bookfacts countdown!), which means that I’ve just come off reading my entire book aloud for the first (and also last) time. I always do this during copy edits, read each word from beginning to end. It’s more time-consuming, to be sure, but it’s also a necessary step for me. First, reading aloud makes it easier for me to catch technical issues like typos and repeated words. Second, it allows me to hear (and feel) the rhythm of a story, from the plot beats, to the dialogue, to the way sentences flow in and out of one another, to the meter of a phrase or even a single word. Rhythm, according to literarydevices.net, is all about stressed and unstressed syllables, which is a rather simple way of looking at this very interesting writing tool. Rhythm, for me, is like pacing. Does the story feel fast or slow? Do the sentences feel frenetic or leisurely? Is the energy of a scene high energy or low? Are the sentences getting the breathing room they need, the room for a thought to ring out before the reader moves on? Or, conversely, are they running together, jostling for space, when the story needs to be urgent and breathless? All of these questions for me are answered with rhythm, which I think operates at various levels of the writing:

For this week, let’s take rhythm at the level of the paragraph. I think there are two main considerations here: length and white space. With regards to length, in general, longer paragraphs will feel slower. Since, also in general, each paragraph focuses on one topic/character/idea/action, the more words that we devote to that topic/character/idea/action, the more time we spend lingering on it. Shorter paragraphs, then, will feel faster, like our attention flits briefly to something and then away again just as quickly. When it comes to white space, the amount of the blank page we see around a paragraph will also affect how much we focus on it and therefore how weighty or important it feels. For example, if a single word is its own paragraph, surrounded by emptiness, it feels more important, like if it deserves its own line, then it deserves to be given more thought/attention/respect/consideration. In contrast, if a single word is buried in a much larger paragraph, well, then, that single word just kind of blends in with everything else, it’s importance tied more to the words around it than to the word itself. As a case study, I’d like to take a look at passages from the first two chapters of Renée Ahdieh’s YA fantasy, Flame in the Mist, where she varies her paragraph length to create the rhythm of a scene. Here, the main character, Mariko, is in a carriage with a contingent of soldiers to guard her from the dangers of the road and the forest they’re passing through. The gathering of shadows shifted outside, growing closer and tighter. Mariko’s convoy was now deep beneath a canopy of trees. Deep beneath their cloak of sighing branches and whispering leaves. Strange that she heard no signs of life outside—not the caw of a raven nor the cry of an owl nor the chirr of an insect. The first paragraph is longer, four complete sentences, and it lingers on the details of the forest: the encroaching shadows, the darkness and density of the woods, the eerie absence of the sounds of nature. The length of the paragraph here emphasizes the looming feeling of the forest they’re entering, and the amount of space it takes up means that it literally dwarfs the next two paragraphs, which are half as short and centered on Mariko’s convoy. There, the emphasis is on the action (the norimono halting; the horses panting and stamping), and because the paragraphs are so short, these things feel more important, more powerful, and more tense, like there’s a lot more riding on them than the longer description of the forest above. The next chapter, too, begins with short paragraphs, as Mariko wakes from being knocked unconscious in her litter. Mariko woke to the smell of smoke. To a dull roar in her ears. There’s this quick, almost disorienting rhythm to the paragraphs here, as Mariko regains consciousness. I think perhaps her body understands the danger before she herself can grasp it, because there’s no time for processing in these paragraphs, just: smoke, roar, pain. Because of the length of the paragraphs, these sensations hit us quickly, and because they stand on their own, they also hit us hard. It isn’t until paragraph four that Mariko, I think, realizes what’s happened, and she focuses on the body of her maidservant, Chiyo. Mariko takes the time (and page space) to both acknowledge the dead body and to remember the person Chiyo was in life (“loved to eat iced persimmons and arrange moonflowers in her hair”). The length of this paragraph slows down the scene, here, giving both Mariko and us, the readers, time process what’s happened. But also note the last paragraph: “The same eyes that were now frozen in Death’s final mask.” This technically could have been a part of the longer paragraph because it’s still technically about Chiyo, but here, Ahdieh is giving more weight, in the form of white space, to this single thought: Chiyo is dead. Chiyo is dead forever. Here, we’re no longer lingering over fond memories. We are literally being stomped back into reality. Chiyo is dead. Mariko is in danger. And in the next two paragraphs, the scene picks up the pace again as Mariko begins to assess her surroundings with more clarity. I’d also like to note that paragraph lengths can also act like meter. Two paragraphs of similar length, for example, will feel more even, or balanced, or solid, or plodding, like a spondee (two stressed beats). In our second passage above, “The same eyes that were now frozen in Death’s final mask.” and “Mariko’s throat burned. Her sight blurred with tears.” are of similar lengths, so it feels like they have the same weight: the single image of Chiyo’s dead eyes and Mariko’s grief for her. These things, the paragraph lengths tell us, feel the same in importance. Short-short-long paragraphs can feel like anapests, that kind of driving/galloping/rollicking rhythm, the short paragraphs propelling the reader into the longer ones. Again and again, I think we’ll end up seeing rhythm operating like this across all these different levels of text--come back in the following weeks as we explore sentences, diction, and punctuation, too! I mentioned in Week 4 that one of my only universal pieces of writing advice is always keep learning, which is also, I suppose, a goal I try to live up to. I’m always in search of new ways to approach a story or better ways to plot or develop character. I’ve realized, however, that I don’t end up reading a lot of books on craft. The Writers Journey by Christopher Vogler and Writing 21st Century Fiction by Donald Maas, for example, are the only ones I return to again and again, and the only ones I always recommend. I think this is because I tend to find long, complicated writing tools difficult to actually use. Take character sheets, for example, where you answer dozens of questions about your character. These questions can be helpful and some writers swear by them, but for me, having so many of them to answer completely stymies my creative process. I get so hung up on feeling like I have to have every answer--How tall is this character? What’s their astrological sign/MBTI type? What do they eat for breakfast?--that I just stop writing entirely. Or, for plotting, take beat sheets, where the main points or “beats” of a story are broken down not only by how they function in the narrative but also by what page number you should be at when you hit them. A lot of people use beat sheets religiously, but I’ve tried them and ultimately just find them constricting and overwhelming.

For me, it’s the simple things that work best for my own writing practice. This is why I like that 10 Things exercise from Week 11, or Writing 21st Century Fiction, which is organized by craft issue (like “The Inner Journey,” “The Outer Journey,” and “Standout Characters”) and has a bunch of exercises at the end of each chapter, so you can just flip to the issue you’re working on and pick one or two prompts that work for you. With twelve steps, the Hero’s Journey might be the most complicated tool I regularly use, but after years of studying it in books and other media, it’s almost become second-nature to me, particularly in terms of energy and tension, rather than plot points. More often, however, I use Dan Wells’ Seven-Point Plot Structure (only seven points! for a whole story!). My friend Jessica Cluess, author of the Kingdom on Fire trilogy and the forthcoming House of Dragons, uses a technique called “fortunately/unfortunately” to get the action moving. I took a workshop called “Plot Like a Film” with Tiffany Jackson (author of Allegedly and Monday’s Not Coming) at the Highlights Foundation Summer Camp, and, after later going to her office hours, found that I can think of plot points in terms of how “strong” they are. Can they hold the weight of the rest of the story? If not, they’re not strong enough! Simple. And easy to use. These are the kinds of tools I most often incorporate into my creative process. At the Highlights Foundation last month, I spoke to another writer about world-building, and she expressed some anxiety over the fact that she didn’t have a “bible” (a long, thorough, well-organized compendium of a fantasy world’s geography, history, culture, etc.). I told her I've never used one, and, while I think it could be helpful for keeping things straight and referencing later if you’re writing a long series, I have almost zero desire to make one. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Big, complex tools like this work for some people. They do not work for me. And while I occasionally struggle with I should do this or I should do that, mostly I’ve come to a place where I adopt the tricks and tools that are helpful to me… and leave the ones that don’t. Perhaps this all goes back to my dislike for prescriptive writing advice. Feeling like we have to write a certain way, or we have to use a certain tool, or we have to have an artistic process that conforms to somebody else’s vision of what creativity looks like… well, that’s so much pressure to take on things that may or may not actually be helpful. I think my feelings ultimately boil down to this: If simple works for you, great. If you prefer complex, also great. If you do some combination of the two, great. Use the tools that make you a better, more thoughtful writer, or a more efficient one, or open up the ways you can think about storytelling, or or or… Feel free to leave everything else. |

ARCHIVES

February 2024

CATEGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed