|

I don’t think I’ve made any secret of my love of revision--I almost always prefer taking something I’ve got and making it better to making something from scratch. While I enjoy substantive revisions (I just “threw a grenade” on a couple chapters of my current work-in-progress, picked through the ruins, and built up something entirely new and wholly better), I’ve come to realize that I’m happiest doing line edits. All the big changes have been made. All the plots and subplots, character arcs, and conflicts are already there. And all that’s left are the tiny alterations, the fine stitching, the hand-sewn beadwork, the cutting or replacing of a word, a phrase, a sentence. I don’t think I’m this way because I’m obnoxiously attentive to detail (or at least, that’s not the only reason), but because I honestly believe that telling a story at its smallest level (the level of word, punctuation, space, phrase, clause) is as important as telling a story at the level of plot or character. For me, that’s because these little building blocks do as much work revealing character, building atmosphere or tension, or creating theme as any paragraph, page, or chapter. Which is why I’m so excited about the topic for the next few weeks: diction a.k.a. word choice. I think about diction a lot. My most-used tool in Microsoft Word is “Thesaurus.” Probably 50% of my Google searches are definitions and synonyms. I think the words a narrator or character uses can tell us so much about how we’re supposed to react to what’s happening on the page in a variety of ways we probably don’t even think about as we’re reading but certainly feel, in our bones. In fact, diction is such a huge topic for me that I’m going to split it across three posts: diction and character; diction, atmosphere, and tension; and diction and theme. Each week, I’ll delve a bit more into how diction influences these areas of storytelling, and, by the end of it, I hope you’ll have something new to think about or a new way to approach word-craft. Diction and Character A while back, I took a marvelous class on sentence writing with Nina Schuyler, author of The Translator and, most recently, How to Write Stunning Sentences, who classified English words into “high” and “low” registers according to their etymologies (Greek, Latin, Germanic, etc.). Nina explains this far better than I ever could, but the way I adapted it into my writing practice was this: Some words sound fancier, more highfalutin, if you will. For example: elongate, nefarious, grandiloquent. Some words sound plain, or more unrefined. See: grow, foul, overblown. In the extreme, fancy words can signal to readers that a character is educated, a gesture is affected, a setting is classy. Plainer words can let your readers know that a character isn’t well-read, a gesture is choppy, a setting is rough-and-tumble. But in practice, I think using diction to reveal character tends to be much more subtle. In The Reader Trilogy, for example, Captain Reed, an outlaw captain who prefers action to thought or a fistfight to a deep conversation, would call himself “scrappy,” whereas Tanin, the power-hungry leader of an organization dedicated to literacy, would accuse him of being “pugnacious.” But diction that reveals character doesn’t just apply to dialogue where the characters are talking about each other. The words a narrator uses to describe setting or action can also influence our perceptions of characters. For example, The Reader Trilogy is written in close third-person perspective, meaning that although the narrator is not a character in the story (and so tells the audience about the characters using third-person pronouns such as she, he, and they), the narrator does tell us about the world and events through the perspective of one character (or, sometimes, a different character every chapter). And the words that one character uses to filter their experience of the world can tell us a lot about who that character is and what they value. In The Reader, for example, chapters from Reed’s point of view are told in simple, straightforward language: “Sometimes when the Current was in port, he’d climb the mainmast and stand in the crow’s nest while the sun sank, and as the waters turned golden and dark, he’d listen to the sea. They said the water spoke to him. He knew all the natural harbors, the swiftest currents, how to avoid a squall even when it seemed intent on destroying him. Some people even said he could look at the pattern of the waves and tell you where they’d come from, where they were going” (p. 55). Most of the words are short and plain: “sank,” “golden,” “dark,” “squall,” “look,” etc. I think the longest word in this paragraph is “destroying.” There’s little fanciness to the words the narrator uses to describe Reed or his world, because there’s little fanciness to Reed. He’s a character with rough hands and a rough manner. He considers himself a simple man, and he values forthrightness, people who speak plainly, and things he can see and touch with his own senses. The diction in this paragraph helps to convey all of that about him without the narrator having to spell it out for us. In contrast, check out this excerpt from Renée Ahdieh’s YA fantasy, The Wrath and the Dawn, wherein Ahdieh reveals the nature of one of her main characters, Shahrzad, through her masterful use of word choice: “‘I’m sorry--so very sorry,’ [Shahrzad] whispered to [Jahandar] before striding across the threshold to follow the contingent of guards leading the processional. Jahandar slid to his knees and sobbed as Shahrzad turned the corner and disappeared. A few chapters after this, we learn that Shahrzad is a clever and well-educated character of her kingdom’s upper class. Her father, Jahandar, is a former high official, a “curator of ancient texts” (p. 45), and a current librarian, but I’d argue that we can infer much of her background here, from her diction. Notice the higher register language: “contingent,” “processional,” “resounding,” “cavernous,” and “voluminous.” In the clause “Shahrzad’s feet refused to carry her,” Ahdieh uses “refuse,” of Latin origin, over something like “Shahrzad’s feet wouldn’t carry her,” which conveys the same meaning, except “would” is a lower register word of Old English origin. To put it another way, “refuse” is fancier, so Shahrzad herself is fancier. Before we even learn of her background, we see her exercising an extensive vocabulary, choosing ornate words over plain ones, which already tells us so much about who she is and where she comes from. In short, I think words convey big storytelling things like plot and action, but I love that being intentional with your diction can add so much extra depth to your characterization (and without taking up more space on the page!). Next week: DICTION, ATMOSPHERE & TENSION. More words! I think the words you choose can not only reveal the nature and values of your characters, as we talked about today, but also build atmosphere and tension in a scene. Keep this going with me next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. Words matter. <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. I think writing can be a lonely process. It’s just you and the computer. You and the page. You and the fictional universe you carry inside you at all times.

Or: you and your own mind, your insecurities, your dreadful voices, your fears, and your failures. It’s easy, I think, to feel like you’re the only one who’s going through this, the only one who’s struggling or suffering. And, I think, being an artist, it’s also easy to feel like you can’t reach out, can’t share your negative thoughts and feelings about yourself/your art/your career, because art is a privilege, a luxury, and complaining about it means that you don’t love it enough, you don’t really deserve to do it, and so-and-so would so much rather be in your shoes and so-and-so would be grateful (unlike you), or whatever. It’s easy to think this way, when you’re isolated, to tell yourself these stories about how you’re not good enough, you’re a failure, you’re alone. Which is why I think fellowship, connecting, really connecting, with other writers, is so important for the health of your creative process. I’m on deadline right now, which means that, in general, I don’t do much more than work, sleep, eat, shower (sometimes), work, research, and work. (This isn’t the most healthy practice, and it’s something I’m working on, but for now, it is what it is.) But in the middle of this month of self-imposed relative isolation, I flew to Seattle last weekend for Emerald City Comic Con. If you’ve never been to a comic convention, let me tell you, it is the most glorious, hustle-bustle extravaganza of creators, fans, geeks, and geek-related things. It’s long lines and long days and aching feet and not-great-food and communities of people coming together for something they love with other people who love it. One of my favorite parts of these conventions now, however, is that I get to hang out with fellow writers, many of whom are friends, and many of whom I haven’t seen in a year or more, and we get to talk about our current projects, our anxieties, our aspirations, our fears, our doubts, sharing industry specific things without having to explain them, using this comforting, companionable shorthand. “I’m on deadline.” “OH GOD. YOU CAN DO IT.” There’s something about being around people who know what you’re going through without you having to describe it. Or: being around people who have already been through what you are going through right now (and who can tell you that you’ll make it through relatively unscathed), understanding your titanic struggle with your revision, or your insecurities about the stability of your career in the arts. Or: being around people who, when you tell them something that sounds so petty, so small, because it’s only fiction, after all, it’s only your perception of your readers’ perceptions of you, it’s only your fear that you’ll quickly dwindle into insignificance if you don’t put out another book next year, they never make you feel petty or small. They listen. They get it. They’ve been there. What a gift that is! To know you’re not the only one going through this. To know that it’s normal to be afraid, or to feel like you’re doing it wrong (even though you’re doing just fine). To know that there are people with you, even when they’re not with you, and they’re only a convention, or a phone call, or an email away. I am always reminded of these things, and I am always grateful. You are not alone. Your fears are not unreasonable. Your doubts cannot actually stop you. Your victories are worth celebrating. Your work has value, and so do you. Next week: DICTION. When I was in high school, I learned about diction (word choice) and syntax (word order), and I’ve found that the more I’ve studied craft, the more I think about them. What’s in your narrator’s or character’s vocabulary? What words do they gravitate toward? Do they speak plainly, or do they obfuscate? How do you make them sound educated? Blunt? Colloquial? Pull up a dictionary next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. I believe in you. <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. Sometimes at events, I get asked what I do when I have writer’s block, and I tell them I have two answers: one helpful and one totally unhelpful. The unhelpful answer is that I don’t get writer’s block anymore, or at least I haven’t gotten it in the past five to ten years. The helpful answer, however, is that one of the reasons I don’t get writer’s block anymore is because I’ve accumulated so many tips and tricks over the years I’ve been studying writing that whenever I’m faced with the blank page, I have a tool to help me deal with whatever is stymying me at the time. An exercise. A map. A craft book. Something.

I do think writer’s block is real, and I don’t think it necessarily has to do with how many tips and tricks you have or how long you’ve been doing this or how skilled you are, but perhaps with any number of other factors, including emotional, psychological, or situational ones. But as I haven't experienced this for a very long time, I don't think I'm quite the right person or in quite the right place to discuss it here. I can, however, share some of the tricks I use when I’m stuck on a scene, or a chapter, or a character, when I’m having trouble figuring out what comes next, what turn to take, or how to approach something. I wish I could remember where I discovered this tool so I could credit it properly, but if anyone knows, please let me know (I’m on Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and Facebook) so I can edit this post! This is one of those easy tricks. No need for charts or graphs. Just a blank space and something to write with. And when you’re stuck, just make a list of 10 things. 10 things your character could do in this situation. 10 things they could be feeling. 10 motivations they might have. 10 potential sources of conflict. 10 places this scene could go. Start with whatever comes to mind. Usually, these are the most obvious answers and the easiest ones to come up with. Let’s say your character needs to get into a locked building. How are they going to do it? They could: 1) bribe someone to open it for them, 2) steal the keys, 3) break a window… But once you’ve exhausted the obvious, it gets more difficult… and more interesting. They could: 4) come in through the sewer, 5) jam the door while someone else is opening it, 6) fake a heart attack to distract the guard, allowing their compatriots to enter… And by the time you’re near the end, you start to really stretch your imagination, coming up with wild or even irrational possibilities. They could: 7) buy the building and demolish one of its walls, 8) impersonate a guard or other person who has access to the building, 9) hire a lockpick who might very well double-cross them… The goal of this exercise is to exhaust the boring, uninspired possibilities of a particular problem and to challenge yourself to come up with something unexpected or nuanced or compelling that you wouldn’t have otherwise thought of. Not all of your answers have to be workable. In general, 1-3 will be unimaginative, and 8-10 will be preposterous, but this is, I think, a good thing. Because giving yourself the freedom to write down all the outlandish things that could happen allows you to stumble inadvertently upon the things that are believable or interesting or surprising, often somewhere between 4-7, that will help you get unstuck. I use this trick all the time. It’s great for when I’m not sure what would happen next, or when I’m unclear about what a character is feeling at a pivotal moment, or how to clamber over some narrative obstacle I’ve set up for myself. It gets me out of my own head, and it gets me thinking beyond things that have to make sense to things that could feel right or true for the story. And whenever I’m done with my list, I always have something new to try, and even if I don’t end up going with one of my 10 things, I’ve started writing again, and that’s a win. Next week: FELLOWSHIP. I had such a blast at Emerald City Comic Con this weekend, meeting readers and hanging out with fellow writers, and I can't stop thinking about the importance of friendship! Let’s be in this together next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. Enjoy yourself. <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. When I’m on deadline, I have a tendency to work myself into the ground. Over the years, I’ve come to realize that my process is naturally slow. From that two-year percolation period before I ever write a word to the half hour I will spend writing and rewriting and rewriting a single paragraph because it needs to have the exact right rhythm, it just… takes… time. So when I have a deadline to meet, I am almost constantly worried that I won’t get my manuscript done in time (I often lose sleep over it, which is the opposite of helpful). Do you know that high-pitched ringing, that eeeeeeee, that you sometimes hear when there’s some kind of electronic malfunction going on somewhere? Well, that’s my brain on deadline.

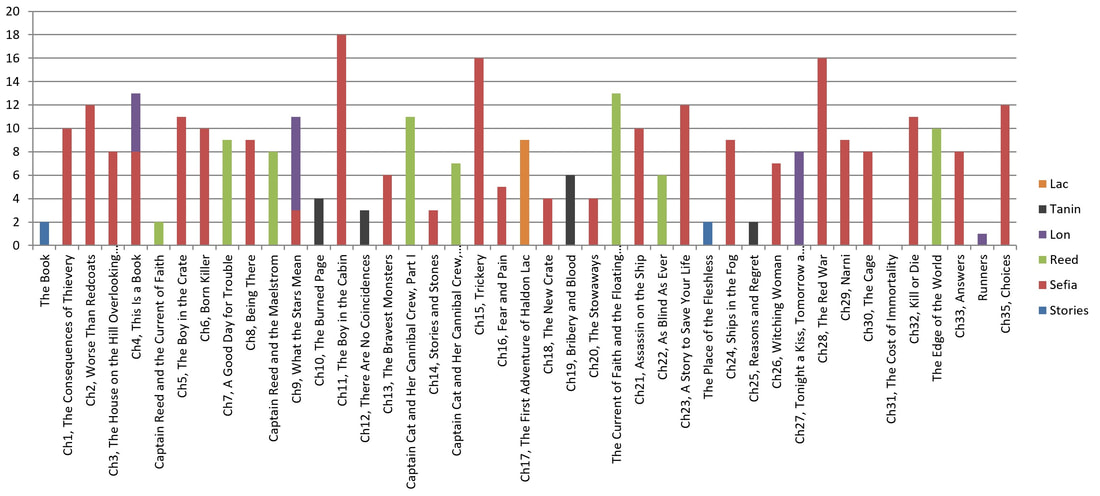

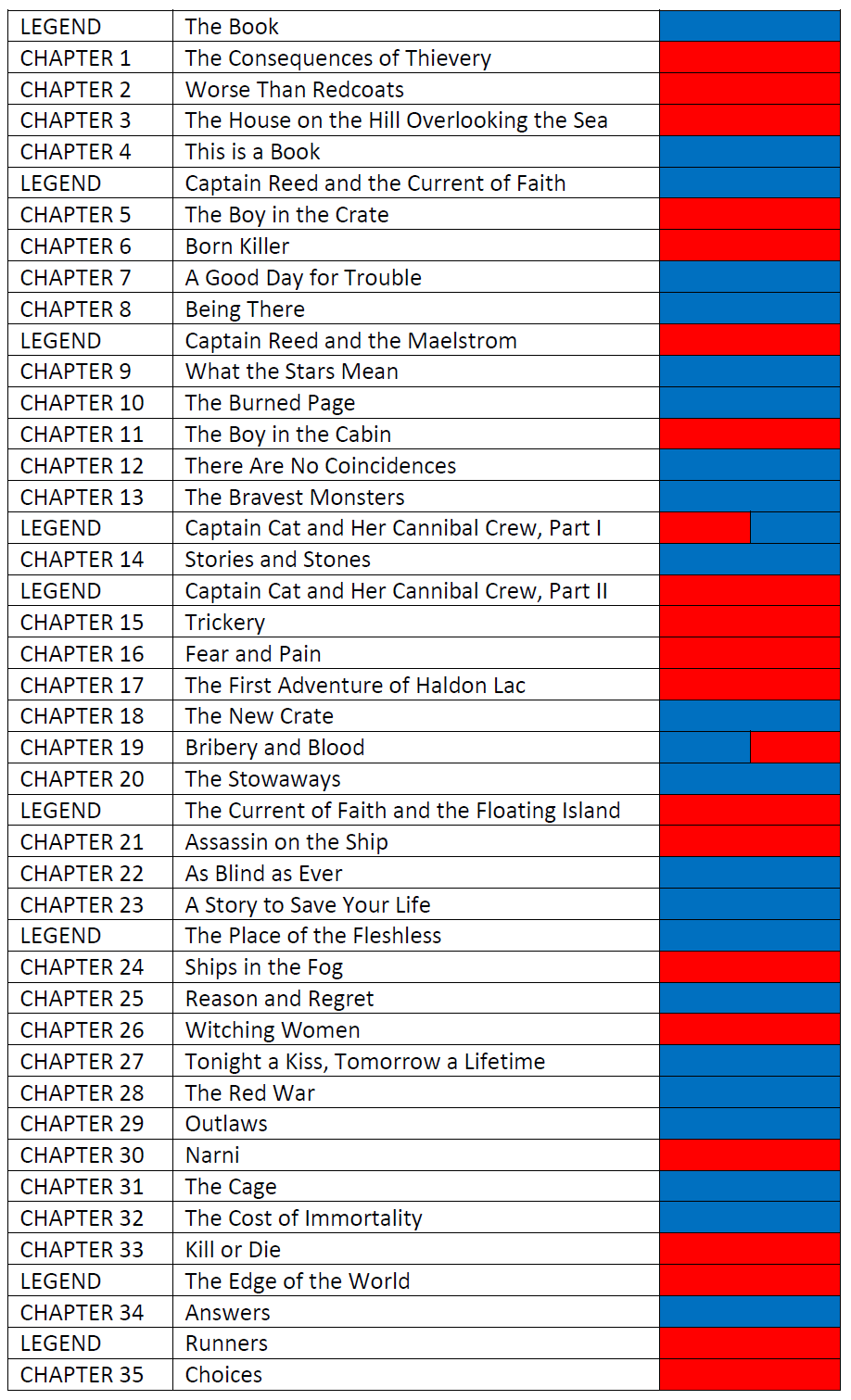

Anyway, this is on top of the fact that I’m also kind of obsessed with work. I was that kid who got straight As in high school (and one B+ in college that haunts me to this day). I love discipline and determination and chipping away at something day after day until it’s done. It makes me feel accomplished and fulfilled, and when I’ve got a task to do at a job I love, I can’t seem to stop myself. All of this to say that when I’m on deadline, I’m stressed out and I work all the time and even though writing occupies this space in my soul that cannot be filled by anything else, I am pretty miserable most of the time. Which brings me, finally, to the topic of this week’s Work and Process: art and suffering. Art is difficult. It’s hard trying to make something new or true or that contributes something to the world. It’s hard holding an entire world in your heart. It’s hard taking some of yourself and packing it into three hundred pages or a sculpture or a song and sending it out the door for strangers to review and critique and judge. It’s hard putting a dollar amount on something that, to you, is invaluable, because it comes out of years of experience and thought and joy and maybe pain. Art is hard. (But I think it would be a mistake to say it’s harder than other work. There are all sorts of demands on people in other professions, and the demands of being an artist aren’t by their nature more important or more intense or more anything than the demands of any other job. I’m just not super interested in romanticizing or elevating the role and the pains of the artist over the roles and pains of other careers.) Still. It is hard. Maybe because there’s no objective rubric for success as an artist? You could make a lot of money, but that doesn’t necessarily make you a good artist. Conversely, you could be making something really and truly beautiful or transcendent or paradigm-shifting, and you might not be able to keep the lights on because no one’s buying your work. Maybe we talk about how hard we work or how much our art costs us because we equate hard work and pain with value. If it takes so long or so much to do something, then it must be worthwhile, right? Maybe we cling to and display our suffering because if we hurt so much, then it must be for a good reason. Right? I was watching the second season of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, an award-winning original series on Amazon, a couple months ago. I have criticisms of the show, but in general, I do find the banter captivating and the acting compelling and the costume design totally enthralling. But there was this one storyline in Season 2 that made me want to throw a chair. It plays out in a number of ways, but here’s a telling example of how it shows up: In Episode 7, the titular character, Mrs. Maisel, charms her way into the studio of a very fancy, often inebriated, notably secretive artist, Declan Howell, who is rumored to have painted something so beautiful, he never shows it to anyone. Quite taken with Mrs. Maisel, however, he invites her behind a hidden door where, voila!, this most beautiful piece of art is displayed. He calls it “perfect” and “the greatest thing I’ve ever made in my lifetime.” We, the audience, never get to see the art, which I think is a great choice, actually, but we are treated to this story about both the art and the artist: DH: This was going to hang in my home. When I had a home. And a family. I had that life. This was… this was going to go there. But that was then. And this is now. I will never have that life. MM: Now wait… DH: I’m not trying to spin a melodrama. I’m being very realistic. The chance for that life is gone. MM: That’s ridiculous. DH: It’ll never happen because everything I have, I put into that [painting]. Nothing left. MM: I think that’s very sad. DH: Well, that’s the way it is. If you… if you want to do something great, if you want to take something as far as it’ll go, you… you can’t have everything. You lose family. A sense of home. But then… look at what exists. In other words, he sacrificed everything to create this exquisite, magnificently beautiful piece of art. No family. No home. No friends (I’m assuming). No joy. That, he is saying, is the tradeoff. That is the cost of art. THe chance at a well-rounded, fulfilling life. Later in the season, there are a couple other events that present this choice between art and happiness, and they all say the same thing: You can be great, but you have to do it alone. You can make great art, but you cannot live a satisfying life while doing it. To make great art, the show seems to say, you have to suffer. Where did this idea come from? This trope of the tortured artist? This cultural narrative we tell over and over again, that art must come at the expense of joy? That genius is the work of pain? Was it Hemingway and his drinking habits? Plath, who died by suicide? Was it Van Gogh (Even though I’ve read that he wouldn’t work when he was ill? Couldn’t produce the works of art we so admire and revere?), who famously cut off his own ear? Why, for something to be good or worthwhile, does someone have to be in pain? I find myself buying into this narrative, this myth, too, to varying extents. Look at how hard I work! Look at how much sleep I lose! Look at how miserable I am! That means I’m doing something important! But as much as I want to be acknowledged (by myself, I think, as much as others) for my hard work, this equation of suffering → art is one that I want to resist. Suffering can be a part of art, sure. I think there’s too much suffering in life (and human history) for it not to be. Huge parts of The Reader Trilogy are concerned with loss, pain, trauma, grief, and I think these aspects of suffering are integral to the project. But suffering should not be the price we pay for our creativity. Something beautiful or valuable or genius should not have to come at the cost of our happiness, health, and general well-being. Art should not always have to be borne of pain or misery. Rather, I would like to lean in to the idea that art can come out of balance, safety, security. Virginia Woolf (who, like Plath and many others, also died by suicide) wrote that in order to make art, a woman requires five hundred pounds and a room of her own, or, the space to create and the ability to pay the bills for that space. She doesn’t require agony. She requires security and a place to work without being interrupted. Similarly, I’ve found that I do my best work, I am at my most productive and my most creative, not when I can’t sleep or when I’m sad, or isolated, or anxious, or unwell, but when I’m functioning, and my basic needs are taken care of, and I have healthy relationships with myself and with other people. I don’t think my creative muse actually wants me hurting or incapacitated. She wants me to show up every day with a clear mind and a healthy body, ready to work. Hardship may be unavoidable--we do live in the world, after all, with other people--and I think it can or perhaps even should, to some degree, influence what we create, but I don’t want to believe that it has to be part of the creative process. I don’t want to believe that suffering is this cost, this toll, this price, that artists must pay in order to make something great. I want to stop glorifying the trope of the tortured artist, because I don’t want our artists and our geniuses and our creative people to have to be in pain for us to reap the rewards of their creativity. I want to continue working on changing the way I think about myself and my work and my process, so that I can have a healthier relationship to my art and develop more sustainable practices, because this is something I love, and I want to keep doing it for as long as I can. Next week: 10 THINGS. I very rarely get completely stuck on a scene, chapter, or project, and that’s probably for a number of reasons, including my stupid ambition or my belief in revision, but it’s also because a few years ago I stumbled upon this one trick that helps me get through most of my everyday quandaries. Lemme tell you about it next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. Stay gold. <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. During Week 5, I mentioned that I am a structure writer--I conceive of my projects first by their shape and only secondarily by their themes, characters, and plots. I think this is connected to the fact that I am a visual thinker. I have to see something to grasp it. This means I print out my drafts so I can view an entire page as I edit it. I make spreadsheets for my revision plans. I lay out my plots with index cards and sticky notes so I can take in the whole complex thing in a single glance. (I wonder if this means I’m also a tactile thinker, since I prefer working with objects that I can physically move around? Perhaps that's a meditation for another Work and Process!) Being a visual thinker also means that I incorporate a lot of maps and charts into my revision process. After I completed one of the many drafts of The Reader, for example, I charted the page count by chapter, like so (minor spoilers if you read the chapter titles): Along one axis, I listed all the chapters, including the legends we hear from the narrator and the passages Sefia reads in the books. Along the other, I tabulated the number of pages in each chapter, color-coded according to which character my close third-person narrator was focused on at the time. With my book laid out this way, I could see which chapters were extravagantly long and which which were skeletally short, indicating pretty clearly where I needed to examine my scenes for excess description, dialogue, or action, like Chapter 11, Chapter 15, and Chapter 28, which all had page counts well above the others. Color-coding each chapter by point-of-view character (at least, roughly--there are some chapters in there that are told from other perspectives) also allowed me to see the distribution of story lines across the whole book and make sure they were evenly woven together (mostly!). Or, in 2014, I was in the middle of the revision round of Pitch Wars, an online contest where unagented writers work one-on-one with more established authors, editors, and other industry professionals to revise their manuscripts, after which pitches and first pages are posted online for agents to review and request, if they so choose. I was struggling with the pacing, the forward movement, the ebbs and flows of tension and action, but I couldn’t figure out exactly where and how I needed to revise, so I made the following chart:: Again, I listed all the chapters. Then, I marked each chapter with a color: blue for a chapter primarily focused on talking, red for a chapter primarily focused on action.

These talking/action categories were something I came up with because I could feel most of the chapters pulling in one direction or another, but I don’t think they’re particularly insightful classifications. Talking chapters were dialogue-heavy. The characters were discussing what had just happened to them, usually in the previous chapter, making plans for what to do next, or using words to try to achieve their goals. Action chapters tended to be hikes, fights, explorations, or escapes--scenes where the characters were doing more than they were thinking or talking. In the years since I came up with this tool, though, I’ve also learned about scene/sequel patterns, which group scenes in a more thorough, purposeful way, but at the time I didn’t have that language or those organizing principles, so, well… talking/action it was! And, importantly, seeing my book laid out this way helped me to pinpoint areas that were just too conversation-heavy, like Chapters 12-14, Chapters 22-The Place of the Fleshless, and Chapter 27-29. In general, these are chapters where the characters were discussing what had just happened to them, making plans for what to do next, or using words to try to achieve their goals. So I went back in, to those blocks where three or more chapters were conversation-centered, and I revised them to cut the extended dialogue pieces, add more knife fights, and turn those blue chapters red! Ultimately, I love shapes and structures, but sometimes I need a little help to understand what I’m doing and how to do it better, which means I have more charts and things to share with you soon! “Maps” will be a recurring topic on Work and Process, as I reveal how I approach other aspects of storytelling, such as stakes, the hero’s journey, and telling a story with multiple points of view. Until next time, fellow storytellers and cartographers. Next week: ART AND SUFFERING. I think it’s hard being an artist for a number of reasons. Putting your dreams and your heart out there for the consuming public. Carrying worlds inside you. Forcing and contorting your process into weird and painful shapes in order to meet your deadlines. But, next week, I’d like to push back against this idea that artists necessarily have to suffer for their art. Necessarily have to be alone. Necessarily have to be in pain in order to make something great. Dispel some myths with me next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. Abracadabra! <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. |

ARCHIVES

February 2024

CATEGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed