|

I’m deep in the labyrinth of another revision this week, and perhaps the most important thing I’ve realized is this: I am nothing if not consistent. I may approach the writing differently for every revision, but I always progress through the same stages of my creative process, the same mindsets and emotional quagmires. I’ve been through them so many times now that I can clearly recognize them, like old friends, or maybe like old archenemies. To tell you the truth, I mostly resent them, but I guess, in the end, they are mine, my stages of revision.

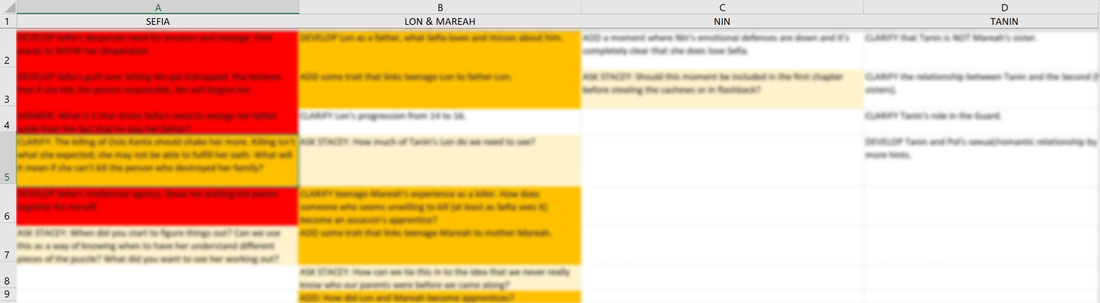

1. Reading the Edit Letter 2. Last 3 Days of Freedom 3. Revision Triage 4. I Have Made a Huge Mistake Part I: Biting Off More Than I Can Chew 5. I Can Work Without Weekends! 6. I Have Made a Huge Mistake Part II: Day 4 Breakdown 7. I’m Not Mad At You I’m Thinking 8. How Is There Still ⅔ Left? 9. Permanent Brain Fog 10. Parks and Recreation Rewatch 11. Midpoint 12. Constant Neck Pain 13. No Time for Exercising (But All the Time for Naps) 14. Dark Night of the Soul 15. Hug a Dog 16. What Day Is It? 17. Cookies Please 18. Am I Laughing or Crying? 19. Every Day 3 A.M. Wake Up (Thinking About the Book) 20. Deadline Met/Anticlimactic Email Sent 21. Sick for a Week (I’m currently in “Am I Laughing or Crying?” so please send your good thoughts my way.) Why is my brain like this? Why can’t the stages of my revision process be “The Best Sleep I Have Ever Had” or “Also Clean Everything”? It’s kind of hellish having to live through some of these things over and over again, it’s also weirdly kind of nice recognizing these waypoints for what they are: temporary. Just part of the process. In the midst of everything, it’s a comfort to know that nothing lasts forever, and however bad my current stage of revision feels, it won’t always feel that way. I am an overwriter. I have been for as long as I can remember. I add paragraphs of description because I can’t write a scene unless I know exactly where everything is and what everything looks like. I start every scene pages before it actually has to begin. My solution to most story problems is “throw more words at it.”

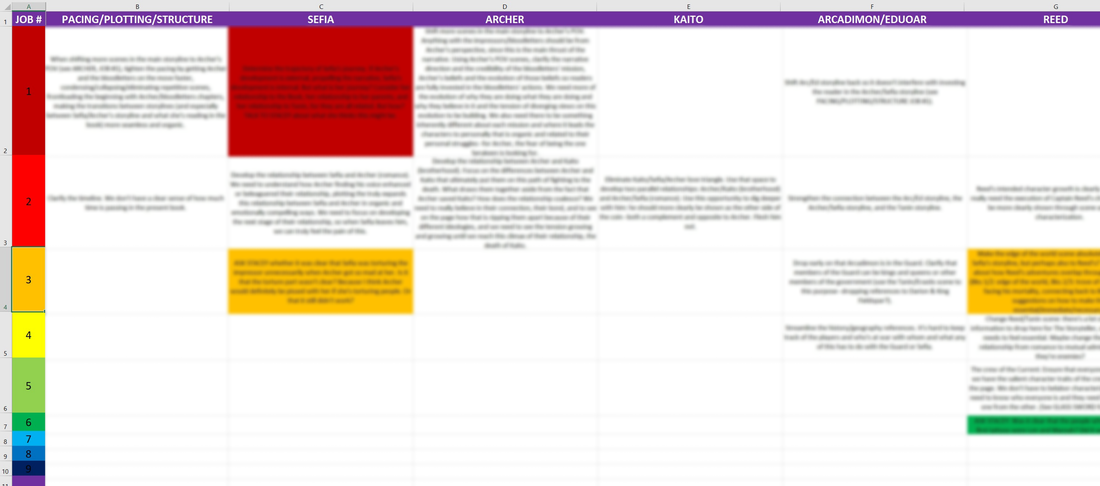

Overwriting is great because it gives me a lot of material to work with when I go back to revise. It’s awful and frustrating because pretty much all of my work ends up too long. When I first started querying The Reader in 2014, the manuscript was 121,000 words. (For reference, at the time, the conventional word count for young adult fantasy topped out at 100,000 words.) Unsurprisingly, I got a ton of rejections. So, after consulting with some lovely and generous professionals, I stopped querying and went back to revising. By the time Pitch Wars, an online mentoring and pitch contest, rolled around, I had cut 14,000 words, so I entered the contest with a 107,000-word manuscript. That was still a little long for queries, but thank the muses, Renée Ahdieh, author of Flame in the Mist and the forthcoming, The Beautiful, was willing to take me on as a mentee. Over the next two months, I cut another 10,000 words, and by the time I signed with an agent, The Reader was sitting at a pretty 97k, 24,000 words shorter than it was when I started querying. As might be obvious from this little anecdote, I’ve become quite familiar with cutting down my word count, and I’d like to share some suggestions in hopes that they’ll be helpful to other overwriters out there. On the internet, I’ve seen advice like: Do a document search for every “just” or “that” and delete all of them. Or: Cut all instances of filtering. A note: Filtering is where a description first has to go through a character’s perspective, like, “He could see the mountains rising out of the fog in the distance.” In this example, “He could see” is filtering, so you could remove it to change the sentence like so: “The mountains rose out of the fog in the distance.” In general, this is the kind of “one size fits all” advice that I find supremely unhelpful. (Like “Show. Don’t tell.”) Every story is different. Every scene or character requires a different touch. So while I think it’s great to eliminate unnecessary words, because it keeps the sentences tight and uncluttered, I believe that some words that seem unnecessary can, in fact, be useful to the storytelling. The repetition of “just,” for example, could be part of a character’s voice, demonstrating their need to have things be simple. Or the use of “that” could be for rhythm and clarity. Descriptions that are filtered through a character’s perspective might tell us that the character is an observer, or they might be a hint that the character’s observations are too biased to be trusted. Instead of these big search-and-deletes, when I want to cut down on word count, I look for bigger passages that don’t serve the needs of the story: Sentences that repeat information or only serve one narrative purpose (see my Rule of Three (But Not Always Three) Things) can be cut, rephrased, or combined. Paragraphs that, while adding interesting character details or beautiful descriptions, don’t contribute to the forward motion of the plot can often be removed. When I was revising The Reader, I’d cut entire scenes or chunks of scenes if they didn’t get right to the point--often the beginnings or endings while I was working my way into a chapter or couldn’t figure out how to end one. Of course, there are also the Big Changes to consider: Sometimes characters can be eliminated entirely, or at least combined with other characters. Sometimes subplots that don’t tie in to the main story can be removed or streamlined. These can feel difficult to tackle, because changing something big often creates a ripple effect of smaller changes throughout the rest of the story, but I’ve often found that the removal of an unnecessary character or plot thread doesn’t affect as much as I think it will. Then, if I still need to lower my word count, I figure out how many words I need to cut, divide it by my page count, and try to cut that many words per page. For example, in a 300-page manuscript that I want to cut 3,000 words from, I try to cut 10 words per page. 10 words at a time often seems more doable than 3,000 total, and it forces me to be really demanding about how I’m using every word on each page. To be honest, though, it rarely works out that I cut my target amount every time. Sometimes I’ll cut more. Sometimes less. Sometimes nothing. But overall, this process, however, not only helps me closer to my target number of words but also polish each page to a shine. In sum, when it comes to my great adversary, the word count, I try to prioritize the needs of the story, adhere to my Rule of Three (But Not Always Three) Things, and go big before I go small. I hope this helps you sharpen your editing scissors, my fellow overwriters. Let’s get to work! Over on Instagram, my friend and colleague, Parker Peevyhouse, author of The Echo Room (2018) and Strange Exit (2020), has been posting videos about different aspects of her revision process, and I’ve found it fascinating. (I particularly love this video about the tent pole, which is an approach I’ve never considered before!) I’ve made no secret of my love for revision, and Parker’s videos have inspired me to talk about an aspect of my own revision process: revision triage. To me, revision triage is the process of identifying the varying levels of difficulty in a revision, from the hardest, most time-consuming edits to the easiest, breeziest, just-needs-a-trim-here-or-there alterations, so that when I start revising, I can tackle the biggest and most difficult changes first and gradually move toward the smallest. That process takes a few days to a week, and it usually looks like this: 1. If I have an editorial letter covering the larger patterns and overarching problems of the manuscript as a whole, I’ll read that first (and only once). Edit letters generally point out the biggest issues in a story, so having these on my radar early gives me a way to think about how they all relate to each other and how they might change things in the story once I start tackling them. 2. I’ll set the edit letter aside for 1-3 days, depending on a) what my deadline is and b) how much time it takes me to start having ideas for how to approach the revision. Sometimes I get ideas quickly. Sometimes I have to get ideas quickly because I’ve got to turn my edits in very shortly. But for me, that little window of time is essential for not-doing, for not thinking directly about the work that’s to come so that the ideas from the edit letter can settle and come together in a way that makes sense to my brain. 3. Once 1-3 days have passed, I’ll read the edit letter again, making notes about how to tackle the various issues. This is the beginning of the actual organization process, and it almost always concerns those big, time-consuming edits, so I try to be as clear as I can about how to implement the changes. 4. Then, I’ll read the manuscript from beginning to end, including notes and marginalia from my critique partner(s) or editor. During this read, I’ll STET advice that I already know I won’t be taking, incorporate suggested cuts I know will make the story better, and jot down potential alterations or notes for later. I try to do this quickly, on instinct, using my vision for the story and my thoughts from the edit letter as a guide. I’ll often also write notes at the beginnings or ends of each chapter, summarizing changes that affect the whole chapter instead of just a paragraph or a page, so I can keep track of them later. For me, the purpose of this read is to take in the entire narrative at once, and if I allow myself to linger on one section for too long, I start to lose track of the arc of the whole story, so I try not to take too long with it. I can’t go too quickly, though, because this read of the manuscript also gives me a sense of what the middle-level revisions are going to have to be and what sections need only minor polish. 5. Now, please allow me to introduce you to my extreme Ravenclaw tendencies. Once I have notes from my edit letter and from my review of the manuscript, I go into triage mode. I make a color-coded spreadsheet to group my revisions by the biggest to the smallest, a sort of map for my revisions to come. Above is a revision map for The Reader that I made in 2015. It’s grouped by character (across the top), and then by severity of changes, with the most severe in red and the quickest to address in white. I did a similar map for The Speaker in 2016. As before, I’ve grouped changes by issue and character across the top, but this time I’ve added colors down the side, starting with dark red for the most work and moving toward purple for the least. This map started out much more colorful, but as I went through, I started switching revisions that I had already accomplished to white, which made it easy to track what I’d already accomplished and also what was still to come. This is a revision map for the project I’m currently working on. As before, there are changes by character, but this time I’m also grouping them by different types of changes along the left-hand side. My triage color-scheme is less complicated now, with only five colors: red, orange, yellow, and green, and purple for reminders or other issues. I’m continuing to white revisions I’ve already completed, but this time I’m also graying out revisions that I want to put a pin in for next time. Every revision triage results in a slightly different revision map. People say each book teaches you how to write it, and I've found that to be true of revising as well as for drafting. Each story needs to be told in a different way. Each round of edits has different requirements. But for me, this process always boils down to the color-coded spreadsheet, the categorization of different types of changes. That's what gets me through. Sometimes it feels like this process of revision triage takes too much time, especially when I’m on deadline, but ultimately, it’s so helpful to me to have an overall sense of where the story is headed, what it’s going to look like when all the threads are tightened and all the extra stuff is cut. It helps me to prioritize issues that will create ripple effects in the narrative, so I change things once instead of over and over again if I try to tackle a bunch of little things first. And finally, it makes me feel like I’m moving forward, breaking down even the big tasks into smaller parts, so I can cross them off like little victories in the long slog of revising a novel. Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. The other day, I was visiting with my friend, Evangeline Crittenden, a multi-skilled actor, director, writer, and musician, whose latest projects include Pepper & Snatch’s Cowboy Cabaret (next show June 13th at the Bang Bang Room in Downtown LA!) and the dream-pop duo, Glamour Pony, and during one of those meandering, thought-provoking conversations that last for hours, we started talking about the necessity of audience participation in performance. A performance shouldn’t spell everything out for you, we agreed, shouldn’t tell you exactly how to feel or think or process, shouldn’t smother you with its own interpretation until you cannot breathe. (I do want to say that this could all be a matter of personal taste, though. We like what we like and create the way we create. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯) This discussion got me thinking about the 2005 film, Hitch, starring Will Smith as a dating coach who teaches men how to get the women of their dreams into relationships. I don’t recall much about the movie, and given what I remember about its premise, if I saw it again today, I don’t think I’d like it much either, but this one scene keeps coming back to me: Hitch is teaching Kevin James’s character, Albert, how to get to the first kiss at the end of a first date, and he says, “The secret to a kiss is to go ninety percent of the way, and then hold.” Go ninety. Then stop. Wait for the other person to go the last ten. Here’s what I like about this idea: giving the other person the opportunity and choice to participate, inviting them to bring something to the interaction between you. The percentages may vary, but I think maybe this advice applies not only to kisses but to performance and writing as well. Once, in a creative writing workshop, a colleague told me that I didn’t have to land so heavily on each paragraph. I didn’t have to hit so hard. I could just let the words ring for a while. At the time, I thought, Uh, no. I want every word to land like a punch. Or like a steamroller. To this day, my solution to most of my writing obstacles is “throw more words at it.” One hundred or why bother, amirite? Since then, however, I’ve come to appreciate that space between ninety and ten, that restraint, that gap between the thing and the audience, the place where meaning resonates. Poets do this beautifully, I think, utilizing line breaks and white space, creating breathing room on the page, places for the words to ring, gaps that ask the reader to make their own connections or to imagine outside of the poem. I love rereading Danez Smith’s poem, “summer, somewhere” (excerpted here) from their collection, Don’t Call Us Dead, for example, not only because it’s beautiful and painful and powerful and and and... but because the lines ring: paradise is a world where everything Ring. do you know what it’s like to live Ring. It’s stunning, the way the words take you right to the edge of spelling it out, but don’t. The way the reader has to piece together the rest. Has to take that leap into meaning. Has to think (and I think also to empathize and connect). I think that’s more powerful, in a lot of ways, than words that wash over a reader, overwhelming them, because it invites a more active participation, because it creates a more interactive experience. There is, of course, a time for creative work that does most or all of the work. There is also a time when a driving, steamrolling sort of narrative style works better than a spare, restrained one. (Maybe that’s a topic for a future post?) But I love that breathing room between the art and the audience, because I think it means the audience comes out of themselves, in a way, isn’t insulated from the creative work but part of it, forming these connections, building bridges. Next week: EGO. For the past few months, after the biggest crisis in confidence I’ve experienced in probably ten years, I’ve been thinking about the role of self-confidence in art. When is it necessary? When will it ruin you or your creativity? How can we use it and not let it overwhelm us? Join me me me me me next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. I’ll go ninety. You go ten. <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. Well, hello! After two weeks of meandering toward this topic, we’re finally talking about significant concrete detail. It’s funny--I always thought of significant concrete detail as this fundamental concept, like, oh, okay, I need to describe things, check and check. It’s one of the first things I studied in Introduction to Creative Writing, and although it’s stuck with me all this time, I don’t actually think I really understood it until recently. Because it’s important, but it’s actually not simple at all. Every time I tried to write about significant concrete detail, I realized I first had to write about something else. Scene and summary. Sensory detail and abstraction. My rule of three (but not always three) things. Don’t worry, though, we’re going to break it all down together. First, let’s clarify what I mean by detail. In my mind, a detail is a description of something in the scene, usually a part of the environment, a character, or an action. In this definition, details aren’t summary, nor are they dialogue or thoughts. Including a detail would be talking about that red chair in the corner or about that dancer moving across the stage, but the backstory of the chair or the dancer’s internal monologue. Then, significance. For something to be significant, I think, it must be relevant to the story you’re telling. It must contribute, in some way, to the forward motion of the narrative, to the development of the character(s), to the atmosphere of a scene, to the conflict, to the stakes, etc. For example, let’s look at this passage from Emily St. John Mandel’s adult literary post-apocalyptic novel, Station Eleven, wherein one of the main characters, Kirsten, is describing her backpack and the few belongings in it (pg. 66): Her backpack was child-size, red canvas with a cracked and faded image of Spider-Man, and in it she carried as little as possible: two glass bottles of water that in a previous civilization had held Lipton Iced Tea, a sweater, a rag she tied over her face in dusty houses, a twist of wire for picking locks, the ziplock bag that held her tabloid collection and the Dr. Eleven comics, and a paperweight. Everything is significant here. The backpack (“small,” “child-size,” “with a cracked and faded image of Spider-Man”) tells us first that Kirsten doesn’t need many belongings, because they will fit in such a small bag, and second, that although she is an adult walking the ruins of human civilization, she’s also still clinging to her past and the childhood that ended, essentially, at the same time the world did. The list itself tells us something about her, too. She’s economical. She carries what she needs to survive but not much more. And she has the ability to survive on very little. Finally, the last two things she carries, a tabloid and comics collection and a paperweight, not only tell us that Kirsten is fascinated by and years for the world she never really got to know, but they also tether her post-apocalyptic storyline to the two other storylines in the novel: that of a lead actor in a pre-apocalypse production of King Lear and that of a paparrazo-turned-EMT during the flu outbreak that annihilated most of the global population. I think this is a good time to talk about My Rule of Three (But Not Always Three) Things, which is that everything you put on the page must fulfill at least two or three narrative purposes. They can immerse the reader in the scene, sure, (that’s one), but they also have to create atmosphere, ratchet up the tension, reveal character, generate conflict, increase the stakes, develop theme, etc. If something (a detail, a bit of dialogue, anything) isn’t doing this story work, then it can probably be cut or exchanged for something that will pull more weight. If you count the meanings we’ve already discussed (two for the backpack, three for the list itself, two for the collection and paperweight), the above passage from Station Eleven already accomplishes seven things. But we can also examine each detail individually to see how much it accomplishes. The “glass bottles of water that in a previous civilization had held Lipton Iced Tea” is a long phrase for what could have been just “bottles,” “glass bottles,” or “Lipton Iced Tea bottles,” but the long and slightly stilted phrasing tells us that perhaps Kirsten doesn’t actually remember what Lipton Iced Tea is, or even what iced tea tastes like, so there this also this disconnect between her/her current world and her memory/her old world. The “red” of the backapck, in contrast, doesn’t contribute nearly as much. Different details can do varying amounts of work, but overall, this single sentence tells us maybe a dozen things we need to know about the story. Everything does more than one job. Everything contributes more than one thing to the storytelling. Now, before we get into concreteness, I’d like to quickly dip into the difference between sensory detail and abstraction. Sensory detail is, as you might expect, detail that evokes the five senses (smell, touch, sight, sound, taste). A peppery scent on the air. A velvety sky. A howl in the bones. These are sensory. You can almost smell/feel/hear them. Abstraction, on the other hand, is more vague. Abstractions are often emotions (love, fury, distaste, consternation), and by themselves, they often rely on a reader’s existing ideas and expectations rather than generating or evoking new ones, so they can lack the power and originality of sensory details and can come off as cliche. (This isn’t to say not to use abstractions at all. As I mentioned in my post on writing advice, I dislike writing dogma and prefer to figure out how to use different writing tools in effective ways. As a tool, abstraction can work really well in conjunction with sensory details, for example. Do what’s best for your story!) Okay, so, to return to our exploration of significant concrete detail, concrete details are ones that are sensory. They put the reader in the middle of a scene and invite them to feel, see, and hear along with the characters. Let’s take another paragraph from Station Eleven, in which Kirsten and her friend August are on guard after having left a creepy cult town. At this point, they think they’ve heard something in the forest (pg. 136): August and Kirsten set off as quickly and quietly as possible in the direction of the sound. The forest was a dark mass on either side, alive and filled with indecipherable rustlings, shadows like ink against the glare of the moonlight. An owl flew low across the road ahead. A moment later there was a distant beating of small wings, birds stirred from their sleep, black specks rising and wheeling against the stars. Instead of using summary to tell us that the characters are on edge (abstraction) because they’re afraid (also abstraction) they’re being stalked, the author instead uses significant concrete detail. There’s this focus on sight (or lack thereof): “dark,” “shadows,” “glare,” and “black.” The simile “like ink” feels tactile to me, that particular cool fluidity of spilled ink, but that, too, is about the impenetrability of the night. And there’s an emphasis on sound as well: “indecipherable rustlings,” “distant beating of small wings.” I’d add “birds stirred from their sleep” too, because the repeated “whirr” sound of the words “birds” and “stirred” also evokes a particular small, fast sound. To put it all together, these concrete details are significant, because they create both atmosphere and tension. In this scene, the characters are unable to see very far in the dark woods, but because of the smallness of the sounds, the things in the woods feel very close. It’s unsettling, knowing they’re not far from possible threats but not knowing exactly where those threats are. The question, Has the cult come after them? doesn’t even need to be asked, because it’s already evoked more powerfully in these details. Kirsten and August are thinking it. The reader is thinking it. We’re all crouched in the dark, together, listening and wondering what’s out there. *chef’s kiss* Next week: SPACE TO BREATHE. I’ve been thinking a lot about the role of emptiness in the creative process. The necessity of white space on the page. The gaps in which we make meaning. Breathe with me next Sunday at tracichee.com and/or post your own responses with the hashtag #workandprocess. Inhale. Exhale. You’ve got this. <3 Work and Process is a year-long journey of exploring and reflecting on the artistic process, craft, and working in a creative field. Each Sunday, I’ll post some thoughts, wonderings, explanations, and explorations on writing and creativity, and by the end of it, I hope to have 52 musings, examinations, meanderings, discoveries, bits of joy or inquisitiveness or knowledge to share. In each post, I’ll also include a topic for the following week, so if you happen to be inspired to question/wonder at/consider your own work and process, you’re welcome to join me. We’ll be using the #workandprocess hashtag across all social media platforms, and I hope we find each other to learn and connect and transform on our creative wanderings. |

ARCHIVES

February 2024

CATEGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed