|

I think we hear a lot about how "good" & "obedient" the Japanese Americans were in WWII, but the incarcerees were not a monolith. They were from diverse backgrounds & held diverse opinions, and rather than submitting to their unjust treatment, a great many of them resisted.

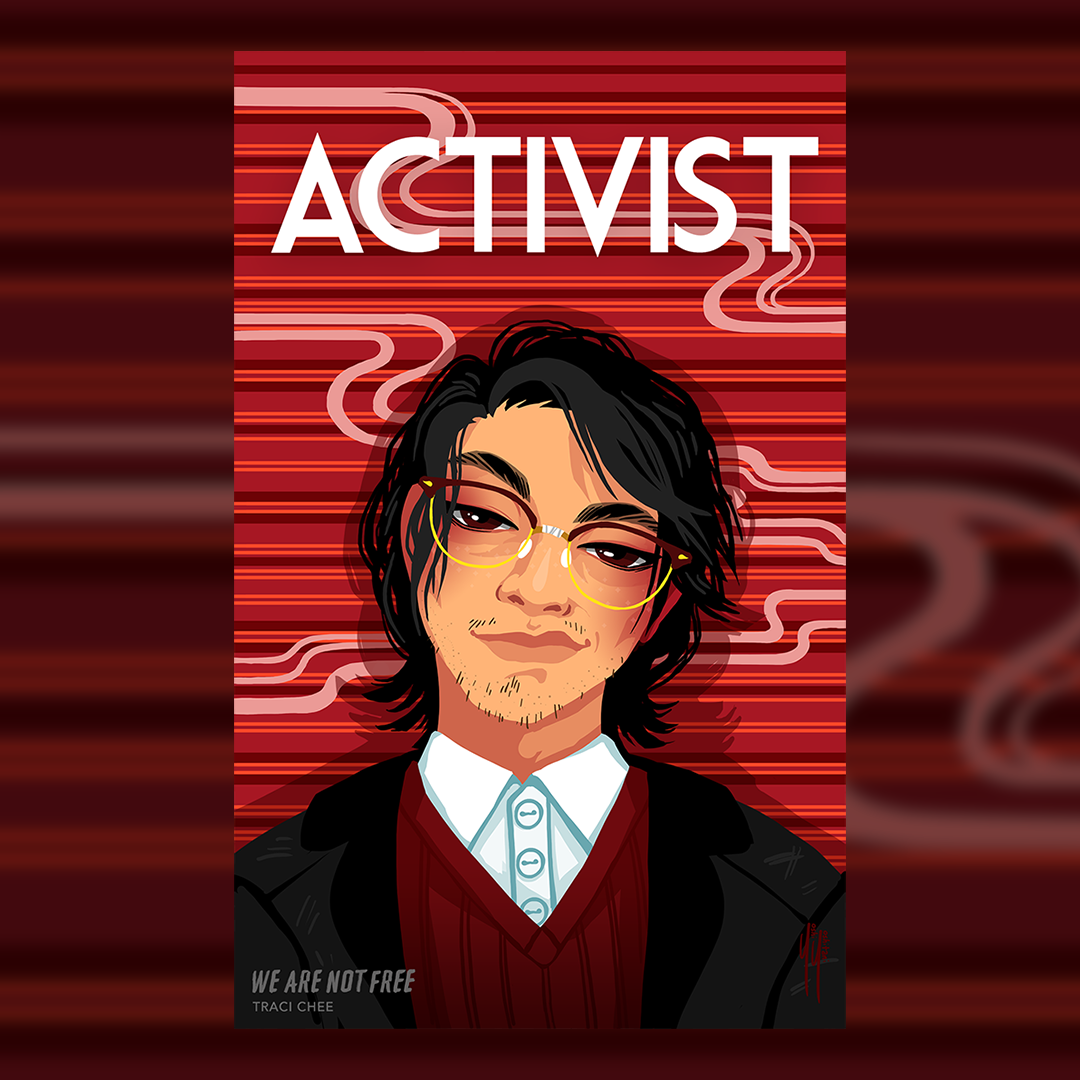

If you haven’t read the first three parts of this series, you can read them here: I) the mass eviction II) the temporary detention centers and incarceration camps III) the Japanese-American combat team * In 1943, nearly a year after the mass eviction that forced more than 100,000 Japanese Americans from their homes on the west coast, the US government announced that all incarcerees age 17+ would be required to register their names, backgrounds, and allegiances. This registration, which eventually came to be known as the “loyalty questionnaire,” soon became a source of great conflict among the incarcerees due to two questions: Question #27 asked incarcerees if they would serve in the US military, wherever ordered; #28 required them to “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor.” The wording of these questions led to weeks of confusion and controversy. Some feared feared a “yes” to #27 would enlist them in the military. Others criticized the registration as being “too little, too late.” Many first-generation immigrants were concerned that if they answered “yes” to #28, they would be stripped of their Japanese citizenship--the only citizenship they had--and thus become stateless persons. Some of their American-born children were affronted by the assumption that they’d ever been loyal to Japan in the first place. Despite all of these nuances, however, in the end the federal government accepted only two responses: Incarcerees either replied with an unqualified “yes” to both questions, or their answers were recorded as “no” and “no.” Throughout the late spring and summer of 1943, the divide between those who had answered “yes” and those who were branded “No-Nos” caused extreme tensions between Japanese Americans and with camp administrators. After several violent confrontations, some of which involved the deaths of incarcerees, the Japanese Americans were subjected to another forced relocation, as the “No-Nos” were shipped off to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a camp with higher fences, more soldiers, and heavier artillery to guard the so-called “disloyals” and “troublemakers.” Tule Lake soon became the largest Japanese American incarceration camp of World War II, with more than 18,000 incarcerees crammed into less than 1.75 square miles. Under conditions of overcrowding, inadequate facilities and food supplies, unsafe work environments, and the inevitable differences arising out of so large and diverse a population, Tule Lake became the site of strikes, unlawful detentions, fights, renunciations of American citizenship, and the rule of martial law. This history remains controversial and at times contradictory, but it’s clear that the Japanese American incarcerees were far from a homogenous group of quietly suffering victims. Some resisted their treatment through the due process of the law. Some organized community protests. Some refused to answer the loyalty questionnaire. Some were violent. Some burned their draft cards. Decades later, many of these stories are still emerging, and they continue to demonstrate that resistance is woven into the very fabric of the incarceration. Preorder your copy here or add it on Goodreads! Illustration by Yoshi Yoshitani. Comments are closed.

|

ARCHIVES

February 2024

CATEGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed