|

Continuing my brief series on the history of the Japanese American incarceration, I’d like to talk this week about the camps. When I learned about the conditions in these places, I was shocked. My family went through THAT? Lived through THAT?

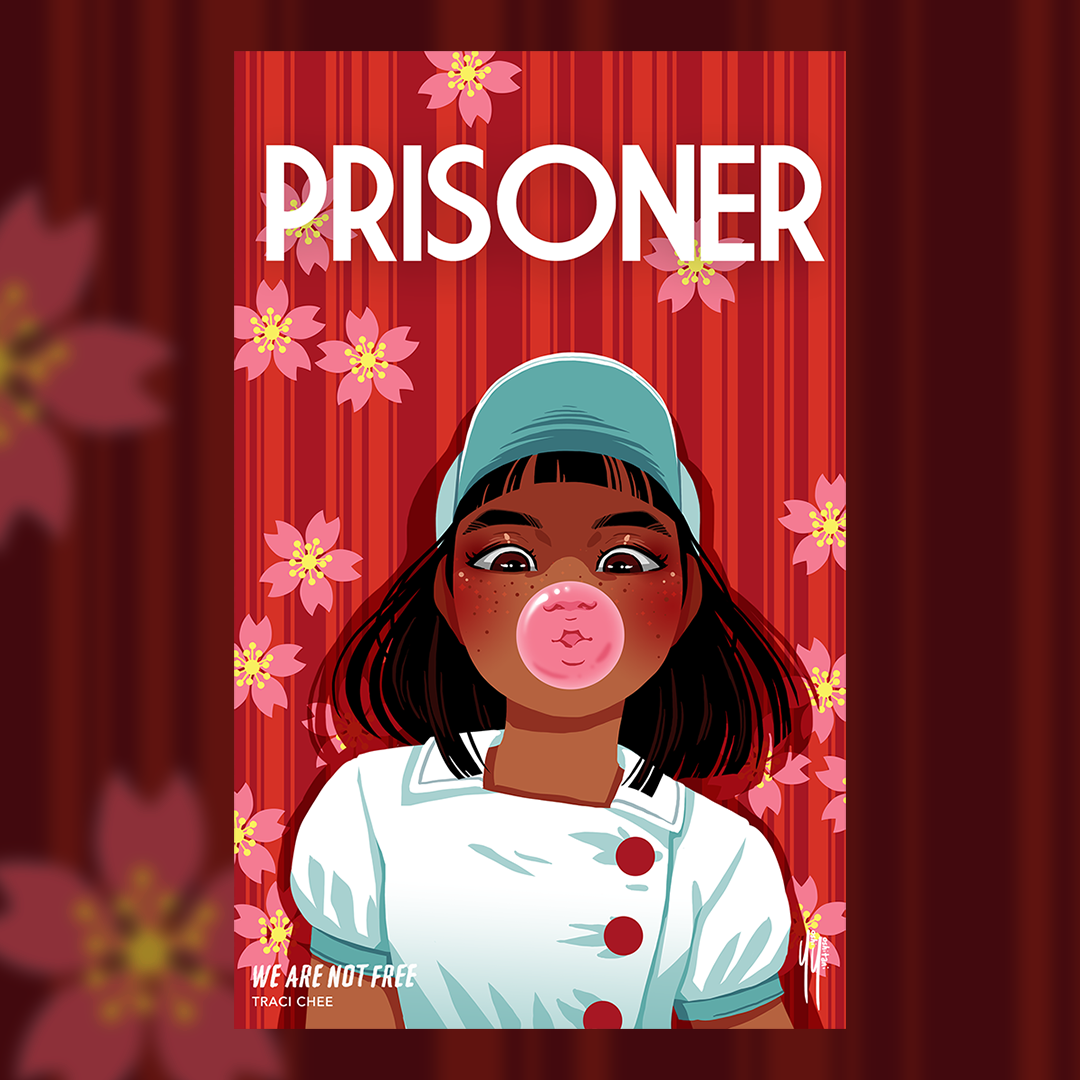

Yes. They did. #WeAreNotFree If you haven’t read the first part of this series, you can check it out here: I) the mass eviction * After being forced from their homes in the spring of 1942, more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated in seventeen temporary detention centers throughout the western United States. Surrounded by barbed wire, watch towers, and armed soldiers, these American citizens and their immigrant parents were subjected to substandard living conditions on top of the stress and trauma of losing their homes. Many of the detention centers were former race tracks, where incarcerees were forced to live in horse stables, hastily white-washed and still stinking of manure--one family to a stall meant for a single animal. Suffering from both lack of privacy and of freedom, they ate in overcrowded mess halls, brushed their teeth in troughs, and used communal latrines and showers without partitions. Despite appalling conditions, however, on the whole incarcerees did what they could to make life more bearable. They built furniture out of scrap lumber, established schools and libraries, formed representative organizations to oversee camp affairs, held dances and concerts, and showed films. Later in 1942, incarcerees were shipped to more permanent camps farther inland. Located in desolate, isolated locations in eastern California, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas, the camps were composed of “blocks” of tar-paper barracks, dirt roads, and communal mess, bathing, and laundry facilities--all encircled by barbed wire fences. While conditions in the incarceration camps were generally better than those in the temporary detention centers, many incarcerees disembarked from cramped, stuffy train cars to find that the camp facilities were still incomplete, and their barracks lacked insulation, proper ceilings, and coal stoves for heat, or that their barracks had not yet been constructed at all. The Japanese Americans again attempted to make the best of their situation, planting gardens, forming cooperative stores, and finding other ways to occupy themselves with work and recreation. But the crowded confines, the knowledge that their civil rights had been violated, and the lack of assurances about their future in the United States caused unrest and conflict, both between incarcerees and with the white administrations overseeing the camps. For three years, until the exclusion orders were lifted in 1945, incarcerees were prevented from returning to the west coast, which meant that many Japanese Americans were forced to live, die, graduate, give birth, bury their parents, get married, forgo college education, learn to drive, and celebrate and mourn thousands of other milestones while unjustly imprisoned. Preorder your copy here or add it on Goodreads! Illustration by Yoshi Yoshitani. Comments are closed.

|

ARCHIVES

February 2024

CATEGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed